Episode 3 Bonus Content

Episode 3 Transcript:

[00:00:00] Tyler McCusker: =50 years ago, 591 American prisoners were saved and brought home, ending the decade long Vietnam war. Today, many of them are still with us and willing to share their stories of horror honor and the perseverance of human spirit

from the Richard Nixon Presidential Library. This is captured shot down in Vietnam.

TITLE MUSIC SWELL

[00:01:00] [00:02:00]

[00:02:43] Tyler McCusker: You've now heard the backgrounds and shot down stories of two men, Commander Everett Alvarez, Jr. In 1964 and Captain Eugene Red McDaniel in 1967. Since they were captured three years apart and sent to different prisons, their [00:03:00] experiences were certainly individual. In fact, all POWs had different and defining experiences based on their health conditions.

Willingness to talk, encounters with North Vietnamese guards and other factors.

In In this docuseries, this show, we're using the plight of these two men to highlight and demonstrate what the hundreds of prisoners went through and overcame since many of them unfortunately cannot tell their tales. Today.

On this episode, we focus again on Everett, the very first prisoner captured and his early adaptation to his North Vietnamese captors, as well as their adaptation to him.

We begin where we last left him floating in the Hanoi. After . Ejecting at mock one, having just let his wedding band sink to the bottom of the ocean so his captors wouldn't use his wife against him.

[ beat]

* *

r WATER SOUNDS SWELL AND FADE. BRING IN NEXT BED

[00:04:00] [00:05:00] [00:06:00]

When I was captured, I was just, to be honest, totally bewildered. I was in shock. My body was in shock as I had just ejected at a very l ow altitude and very high speed.

In thinking back, I remember a lot of things, but the one thing that stands out is I'm in the water and I'm looking around.

It dawned on me that today was Wednesday, and on the ship, it's roast beef night in the ward rooms. And I realized I was gonna [00:07:00] miss roast beef night. Now don't ask me why I thought that. All these crazy thinking things.

After things sort of cleared up and I saw the boats around me at a distance. The Vietnamese, little fishing boats about four or five people Well, they were all [00:08:00] militia.

They wanted me to surrender. so I eventually put my arms up they came close hauled me . Aboard

[ beat]

[00:09:00] [00:10:00] [00:11:00] [00:12:00] [00:13:00] [00:14:00]

I, I couldn't understand what they were saying

at that point. For some reason I started talking to them in Spanish. Same what, what in Spanish que.

When I was relating this story later to one of the guys in the camp, one of the fellas that. Was the p o w and one of the cells said, oh, hey Ev,, you should have told 'em you were a lost Spaniard looking for gold.

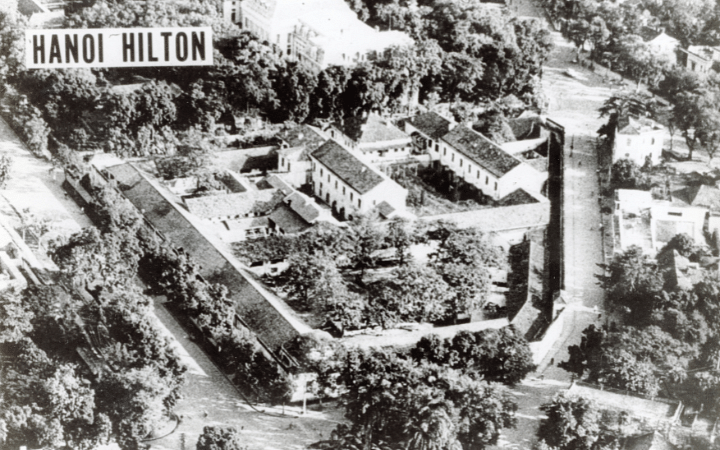

[00:14:40] Tyler McCusker: Everett was taken to a small town Vietnamese jail. At that time, he thought it was the worst place he would ever lay his head, but that was only because he hadn't yet been taken to the Hanoi hilton.

[00:14:50] CMMDR. EVERETT ALVAREZ: People were coming in and taking my picture.

[00:14:57] CMMDR. EVERETT ALVAREZ: they're big on taking pictures.[00:15:00]

[00:16:00]

[00:16:59] CMMDR. EVERETT ALVAREZ: [00:17:00] They led me to a cell opened it up SFX CELL OPEN CREAK I stepped in and there were two Vietnamese prisoners there,

and by this time, the exhaustion set in.

[ beat]

There was a platform and the two individuals, as I realized it was their bed. A wooden platform straw mats, on it. At the end of the platform was a long bar

my . Ankles were in , like a horse collar, , ankle irons, we called So you couldn't move , your legs. I saw that they were putting my feet in these, and then they ran the bar through.

[00:17:50] CMMDR. EVERETT ALVAREZ: And it locks on the outside of the cell.

[00:18:00]

[00:18:40] CMMDR. EVERETT ALVAREZ: I, I just sort of just plopped back and I was out like a light.

[00:18:53] CMMDR. EVERETT ALVAREZ: [ beat silence]

I woke up the next day, I could hardly move my body really cuz of the [00:19:00] strain..

They walked me to, interrogation, first time [

[00:20:00] [00:21:00] [00:22:00] [00:23:00]

[00:23:00] CMMDR. EVERETT ALVAREZ: 2 Vietnamese officers.

Both spoke English,

[ sting]

I gave 'em name, rank, service number, date of birth. That's what we're supposed to do. And

they said,

why, why? And I said, well, that's all I'm supposed to give you.

They said, you know, according to the treatment of the p o w, they said, you're not a p o w.

[00:23:19] ALVIN TOWNLEY: There's no war, there's no declaration of war.

Interestingly the Americans and North Vietnamese really didn't agree on what exactly a P o W was because there was no declared war between the two countries which, was true,

[00:23:34] Tyler McCusker: Alvin Townley, author, historian, and expert on the Vietnam p o w Crisis.

[00:23:39] ALVIN TOWNLEY: The Americans went to great lengths to not make it a war. The Johnson administration wanted to downplay it,

[00:23:46] LBJ: I've tried to do my best to, uh, I've lost about 264 lives up to now, and I could lose 265,000 quite easy, and I'm trying to keep those zeros down

. [00:24:00] So I've got a pretty tough problem, man. I'm not all wise, I pray every night to get direction and, uh, judgment and leadership, uh, that permit me to do what's right.

[00:24:11] ALVIN TOWNLEY: They really didn't like to use the term prisoners of war because that would really signify there was an actual war. But the US very much wanted North Vietnam to honor the Geneva Convention, which governed the treatment of prisoners of war in war, conditions. so America in some ways was trying to have it both ways you know, have the Geneva conventions be in effect, but also not acknowledge that there was an actual war

[00:24:34] Tyler McCusker: The Geneva Conventions are a collection of international treaties, defining the basic rights of wartime prisoners, including protections for the wounded and sick. They certainly did not allow torture without honoring them. Any treatment of Everett and other POWs that the North Vietnamese desired was fair game.

[00:24:53] CMMDR. EVERETT ALVAREZ: They started telling me how I was going to be facing a, a tribunal. I would be, [00:25:00] uh, punished, maybe executed on and on.

If you weren't a prisoner of war, what was your crime?

My crime was, I had attacked the, Vietnamese people in the military.

[00:25:11] ALVIN TOWNLEY: From the North Vietnamese perspective, these guys, they were capturing were criminals bombing their country illegally.

You know, we had created a lot of damage and, you know, of war. It was an act of war.

It was a, you know, a military action and it was, the Gulf of talking resolution versus the Declaration of War.

North Vietnam was literally getting bombed on a daily basis. And I don't think they really cared that much about Geneva conventions. I think their daily reality was survival. So it was really an interesting situation. The North Vietnamese had some legal ground, you know, not to necessarily honor the Geneva Convention.

But when they tried to get the Americans to, to violate that convention and give them more than their name ranked service number and and date of birth the Americans very much held [00:26:00] to the military code of conduct and the provisions of the GVA convention.

I wasn't answering their questions. .

I didn't want to tell 'em anything,

" I didn't want to tell them anything" should be dry, over nothing, after the bed perhaps playing the entire time before for emphasis. Then you can transition into another bed perhaps.

[ beat or sting whatever]

They took me back to my cell . All I really did was sleep

[00:26:27] ALVIN TOWNLEY: One night, in the middle of the night, here comes a fellow

[00:27:00]

[00:27:57] ALVIN TOWNLEY: one of the officers, , that [00:28:00] spoke English. And he says, look, he says, you are our prisoner.

You are not a prisoner of war, and you don't want to answer any question.

But then he reached in his little bag and he started pulling out,

[00:28:55] ALVIN TOWNLEY: American Magazines, time, Newsweek, US News and [00:29:00] World Report, uh, newspapers, the, uh, San Francisco Chronicle, the San Jose Mercury News and everything had my picture plastered all over it .

All about me, my bio, pictures of my family, a picture when I was in high school where I grew up, what my, you know, my dad's was there.

Well, you know, what do I do now? I said to myself.

And I said, well, so much for name, rank, service number, and date of birth.

It was still middle of night early. they put me in a Jeep

[00:29:35] ALVIN TOWNLEY: [

[00:30:00]

[00:30:24] ALVIN TOWNLEY: 'and we left

I could tell even though I was not supposed to look out. But then, you know, with all the noise of a city.

[00:31:00] [00:32:00]

[00:32:22] ALVIN TOWNLEY: We drove in that afternoon, we pulled into Hanoi.

A building that had a, a big door. Big prison. We later named the Hanoi Hilton.

, I was taken out, I was put into a room and I, I became the first occupant of the Hanoi Hilton, first American p o w.

[00:33:00] [00:34:00]

[00:34:10] ALVIN TOWNLEY: There were several harsh . Elements to imprisonment in the Hanoi Hilton . it was just a, old, nasty prison.

It was never built for holding you know, American pilots. And certainly not as many as ended up in North Vietnam.

It was an antiquated building already in, in the 19 sixties.

Prisoners would say that you could just kind feel the screams of, you know, a hundred years of colonial injustice when you walked in there from all the colonials that were imprisoned there by the French, and, you know, horrible things were, were done to them The cells were small, they were dirty. . people had had their bucket, they had to carry around, So the conditions alone were pretty bad.

[00:34:51] ALVIN TOWNLEY: Of course, at the beginning I was totally bewildered.

, I was not a p o w there was no war. Okay, what am I, what are they gonna do to me?

[00:35:00] Wallo was the name of the prison. It it means in Vietnamese Fiery Forge but, uh, we call it the Hanoi Hilton.

It was a prison. It was full of men and women prisoners, as they told me later. Thieves, women were prostitutes. they were, um, criminals.

when I arrived at the Hanoi Hilton, I was in a room which had access to a little courtyard, on the corner was a latrine. That style where they have little foot stools and you squat and you do what you're going to do. I, so I learned to do that right away.

When I didn't have access, they had a bucket, an old rusty bucket, by the door that led to the courtyard. It had a bed, which was a, a rack, with boards. I put my straw mat there my mosquito net [00:36:00] had a little table with two chairs, but I was, I was locked up

[00:37:00] [00:38:00]

[00:38:03] ALVIN TOWNLEY: .

I mean, that was a big room compared to later on.

I was fed twice a day in the morning and in the evening. immediately, I, the food just didn't agree with me it was hard to digest. = I find it hard to describe. some real greasy stuff, uh, that I found I couldn't eat, but I had to eat. I had to sustain myself and I lost a lot of weight in the first, uh, about the first three, three to four weeks.

At one point I was really feeling sick.

So I asked the guard if I could have, that broth, that tea, it turned out to be like a chicken broth.

And that evening, He came with the food. I figured it, it was a broth. But here I opened it and it was, Sliced bread that was [00:39:00] like french bread and God, I looked at that and I pulled up the other one here was an omelet, a real omelet. And it had french fries you know, the French influence.

And, and I just, I gobbled that down and I started eating that and, and I started to cry. I actually started crying cuz the food was so good. And I, and I just scarfed it down

the first six months was mental torture.

They had started to give me propaganda things to read in, in English and, you know, sheets of paper with stories on it about French colonialism_._

And that's where the, the rub between the North Vietnamese and the Americans started because they, they wanted propaganda statements. They wanted intelligence.

A lot of the purpose of the [00:40:00] propaganda was internal. And maybe they thought that people in Europe or other countries might give some credence to it as well. But don't, I don't think it was that effective in, changing the American's opinion of the war.

It graduated to, recording, making tapes , for the radio.

[00:40:24] ALVIN TOWNLEY: The camp radio, uh, speakers,

Just information.

Whether it was their propaganda or whether it was just American public sentiment, they realized that America was just not gonna tolerate a long and costly conflict in Southeast Asia. And the quicker they could turn American sentiment against the war. The quicker it was gonna end and they could achieve their, their ends

They wanted me to help 'em like I was one of them.

I said, you know, to myself, I can't, I can't do this cuz this, this would be collaborating with them. I can't help, I cannot help them.

[00:41:00] the Americans who lost everything, once they got shot down, they lost everything, except really their sense of honor and their will to survive. _ _ So I didn't answer anything. And they said, will you help us? And I said, I cannot do this, and why not? You know, I mean, we, you know, I said, I, I can't.

And so they sent me back to my cell and I figured, okay, now the rubber's gonna hit the road. [

[

[00:41:28] ALVIN TOWNLEY: A day later, they took me out of that cell and moved me to a smaller cell across, on the other side of the courtyard.

and I was there for about maybe several weeks.

And then one night they took me,

[00:42:00] [00:43:00] [00:44:00]

[00:44:34] ALVIN TOWNLEY: they interrogated me again. And I was not cooperating at all. I, I just couldn't.

so then they took me from that cell to a tiny seven foot by seven foot cell that had the, two beds, concrete beds.

You could put your straw mat on that. There was space about hmm. Foot and a half that you could walk in between. And it was three paces. The [00:45:00] door, three paces, the wall.

And so I said, okay, this is my existence._ _

[00:45:05] Tyler McCusker: [

what were you thinking about that first couple months?

I wasn't thinking much.

I was, uh, um, I wasn't thinking much at all. Uh, and I, you know, I just didn't know I was there and there was, um,

and then, you know, I was feeling pretty down.

That first Christmas, um, was the loneliest Christmas, you know, with my memories.

_[_ _silence beat beat]_

[00:45:38] LBJ: You either get out or you get in. I don't think there's much more neutral. I think we've tried all the, uh, All the neutral things

[00:45:54] CMMDR. EVERETT ALVAREZ: six months after I was shot down, the war was on.

[00:46:00] [00:47:00]

[00:47:59] Tyler McCusker: [00:48:00] Back in Washington during the first six months of 1965, president Lyndon b Johnson was debating whether to turn the Vietnam conflict into a full fledged war.

His vice president, Hubert Humphrey, advised against it. His longtime mentor and friend, Senator Richard Russell, advised against it under Secretary of State. George Ball advised against it.

His opposers said the war would have to be limited in scope, which meant to them that the. job could not be finished without an open-ended commitment. Much later, LBJ would take accountability for leading many Americans and innocent Vietnamese to their deaths. There's no easy choice when your chief executive of the most powerful country on earth, but the choice to go to war in 1965 was LBJs and LBJs alone.

[00:48:51] LBJ: I held up till February after I came in in November.

I went from November to November, from November to February. But, uh, they, they [00:49:00] kept coming. They just kept coming and I couldn't stand any longer, had to get out or do it. Now I'm doing it a restrained and with the best judgment that I know how.

I got the newsletter that the bombing had resumed and they had shot down another prisoner Bob Shumaker

[00:49:15] Tyler McCusker: _ _six months after Everett's capture, Lieutenant Commander Robert h Shoemaker became the Second American p o w held in the Hanoi Hilton when his F eight D aircraft was shot down by Cannon Fire on February 11th, 1965.

By the end of his captivity, eight years later, almost to the day, Bob would be promoted to the rank of commander and become renowned as one of the most active resistors credited with devising ingenious communication systems like the famed tap code, which we'll explain in a later episode.

[00:49:49] CMMDR. EVERETT ALVAREZ: And I knew when I heard and Bob had shot down and all this, that okay, the war was on.

I confirmed [00:50:00] that cuz one day I, a few days later after that, I'm looking out at the peep hole and you know, and the guy's bringing in the food. Next thing I know he's got my Iraq and another rack.

. I never had contact with him, but I knew he was there

one of the things people sometimes fail to do is, is look at the POW situation _as a _

_human experience_

[00:50:21] Tyler McCusker: In defense of the Northern Vietnamese, some of these prison guards were Everett's age or younger. Many of them had never seen or spoken to an American in their lives, and Everett was the first American inside these walls.

He was adapting and getting* *used to his new life as a P* *o W with no scheduled release and no eventual end in sight

and they were adapting to their role as his captor. Also, without truly understanding why or for how long, although considered the enemy. Some of these guards were just curious, interested, and confused kids.

[00:50:59] ALVIN TOWNLEY: the [00:51:00] POWs were normal people with a great sense of honor and, and mission put in the extraordinary circumstance.

They were just people at the end of the day, and the guards and the interrogators were just people doing their job.

They were basically, uh, young officers, Vietnamese officers that would, become interrogators, English interrogators. And they were practicing their, stuff on us.

Of course, being the first one there, they would try on me and, you know, there was a lot of officers learning English. And so you'd be in there sitting on a stool, listening to them, actually rehearse their English, you know

talking about, , behaving and this and that.

These were guards and officers that probably didn't really wanna be assigned to a prison camp, but they had to show up in the morning just like everybody else and do their job.

After a few weeks they started interrogating me.

[00:51:48] CMMDR. EVERETT ALVAREZ: they said

We are here to learn and we're gonna interrogate you.

And it was at that point that I, I really, banked on the fact that they thought I didn't really know much because I was [00:52:00] so young and I played that up.

They started basic things like name and this, and, I did answer their questions, about myself and biography The interrogations went from one day to the next, to the next, to the next.

and the questions became more detail oriented.

I don't think they viewed Ev as an evil person. they're in the early days there's probably a little more communication between EV Alvarez, and the guards there.

I started fabricating things. .

[ beat]

I says we had jobs, we were assigned jobs and I was so new, I had just reported to the squadron and they said, uh, and what was your job? And I, I told 'em that I was put in charge of the popcorn machine. And the popcorn machine was just something that blew and blew 'em away.

They had no idea what I was talking about.

[00:53:00] [00:54:00] [00:55:00] [00:56:00] [00:57:00]

They wanted to know about this popcorn machine. Oh. So I spent, you know, I spent days talking about popcorn and how it's made, pops in the right. They wrote everything down, but you know what, they had no clue. corn what pop you Popcorn, you know, corn. Corn, the, oh, and I would draw a picture of the corn, little corn things, and you put heat it pops.

When you see somebody every day, like they were seeing Ev Alrez every day, natural human instinct takes over. , they saw somebody who's probably around their own age. Ev was pretty young, and so they just started a conversation to find out about a culture that they didn't really know about. There was just kind of a human, a human . Interest there.

They thought that was so, you know, they'd come back to that and ask about pop the popcorn machine.

Why do you think they wanted to know such trivial things in addition to the big military [00:58:00] questions?

Well, to me that was trivial

to them. It was totally, new and and what have you.

[ beat

over the, you know, period of time I had given them the impression I was a good guy. I was sympathetic to 'em and their cause, you know?

and eventually they caught me in a lie cuz I had said I was not part of the group that, that was to attack.

And I started to sort of cry. Why? And, and why, why did you lie to us? And I says, cause I thought you were gonna kill me. You know? This fellow, my interrogator says, oh, no, no, no. We're not gonna kill you. We want you to learn about us and our cause for freedom against totalitarian oppression and colonialism.

And on. And I, and it hit me. Yeah. They weren't gonna let me die. They weren't going to kill me, cuz I, I was in their news. I was in the news. They had me and it wouldn't look too good.

[00:59:00]

Christmas came close and, uh, I was getting their newsletter, English translation, the newsletters. I read everything. Then there was like the, uh, a delegation that came to Vietnam, to this international conference for all the peace loving countries in the world, uh, you know, to unite against neocolonialists, , aggressors throughout the world.

They came and said, would you like to go meet a delegation? I said, all right. You know, I had nothing else to do and nothing else was on my schedule [TYLER GIGGLE]

[00:59:39] Tyler McCusker: just a few months after being shot down, Everett experienced one of the defining moments of his captivity, one that would reaffirm his commitment to his duty and to his country. One that may be hard for a modern audience to understand, but helps put us into the mind of a member of the American [01:00:00] military, especially one as heroic and honorable as Everett.

[01:00:04] CMMDR. EVERETT ALVAREZ: They took me, of course, to Hanoi and when I got out of the Jeep, I went into a building a guest house, I guess. And* *it was to meet the delegate an American, they told me an American citizen.

When he came into the room, it was a, an African American fellow. His name was Robert Williams and he lived in free . Cuba , he had asked to . See me if he could meet with me.

I'm sitting there across, there's a coffee table and it had fruit and it had cookies and it had stuff. So I'm sitting there stuffing myself with cookies listening to him. [

[01:00:52] CMMDR. EVERETT ALVAREZ: The crux was, he says, would you like me to ask President Ho Chi Min if you could go home with me? I said, [01:01:00] well, sure, go, go ahead. No, no, go ahead.

Well wait a minute. He says, you gotta do something to help yourself too. You gotta write a letter to him and, ask him for your release. I left it at that, the visit was over. I went back and next day here comes the interrogator, so do you wanna write a letter to Ho Chi man asking for your release and how good we have been to you?

You want to tell 'em that? And you understand, you know, the fight for freedom and against the colonialism and, uh, and the aggressors around the world, and the oppressors, and on and on. I said, sure, I'll write a letter. So uh, they gave me paper and pen, and I wrote a letter.

_[ TRANSITION BED_

To whom it may concern. I feel I have, been a, a good prisoner I have, uh, been respectful to the Vietnamese people, and I would like to ask you for my release, to whom I may concern, I'd like to ask for [01:02:00] my release, and I signed it. Oh, then he, next day he came back storming back, boom.

* *

[01:02:16] CMMDR. EVERETT ALVAREZ: You, you, . You know, be so disrespectful. You do not say to the President Ho Chi Minh, you said, to whom it may concern and you didn't say anything, you know, back about the Vietnamese people's fight for freedom and independence and all this and that, and that you are sorry for, you know, your crime and all that.

And I said, well, I'm not gonna say that I'm, you know, I'm not gonna say that. ,

[01:02:38] Tyler McCusker: You see, Everett didn't want to give North Vietnam President Ho Chi Minh, the respect of addressing him by name. He also certainly wasn't going to fabricate or positively exaggerate his treatment. With that letter. Everett may very well have sealed his fate for the next eight years. Would he truly have been sent home if he had written it the [01:03:00] way he was told?

We can't say for sure what we can say. There are few better examples of standing up for what's right and standing up for one's country in wartime than this act of defiance from Everett Alvares.

This moment though would be the end of Everett's honeymoon time in prison. No more conversations about popcorn.

No more friendly guards. The illegal torture would begin starting with the abuse of light.

[01:03:32] CMMDR. EVERETT ALVAREZ: The lights are on all day. The lights are on all night when it's dark. the big effort , in that point of time was to keep my sanity

[01:03:41] Tyler McCusker: When our other hero, red McDaniel would become a fellow prisoner in 1967, he also would get no play time. His captivity dove right into full fledged torture, abuse, and horrific conditions.

[01:03:57] CAPT. RED MCDANIEL: It's like taking a rope and tying a knot into it [01:04:00] and hanging on for six years.

that's a very descriptive term of our captivity.

[01:04:06] Tyler McCusker: Now that you know how these men adapted to the early days of imprisonment, next time we'll tell you what they had to endure and how they managed to survive.

[01:04:16] CMMDR. EVERETT ALVAREZ: When you heard the, the, the guy coming with his keys dangling, especially at night, you knew somebody was gonna go out and you prayed it wasn't you.

[01:04:45] CMMDR. EVERETT ALVAREZ: And if it was you and it was your turn to go do something, whatever it was, you had a, you just had to face it. And if it was somebody else's cell, you prayed for it.

[01:04:57] Tyler McCusker: That's next week [01:05:00] on Captured.